Transfuse to target

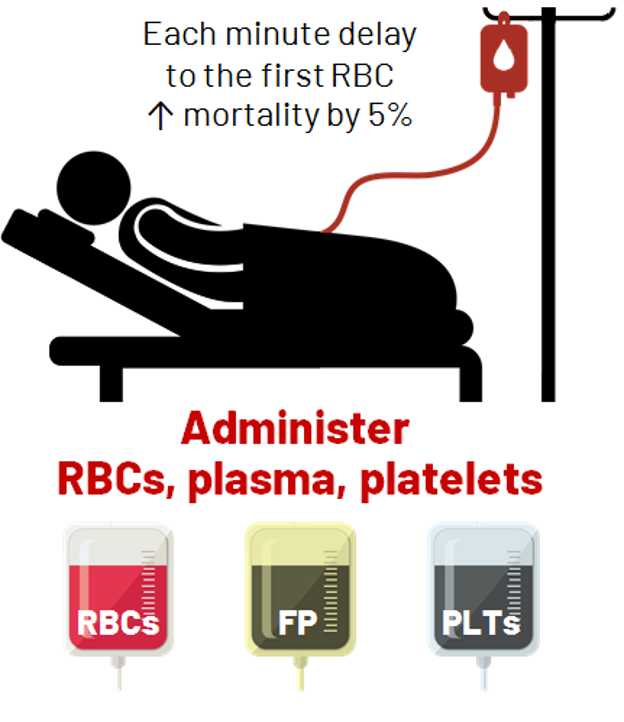

- Start with 4 units of RBCs and then switch to transfusion at a ratio of 2:1 for RBCs and plasma, i.e., transfuse 1 unit of plasma for every 2 units of RBCs

- Administer platelets and fibrinogen replacement as per patient laboratory results

- Switch to goal-directed transfusion as soon as practically possible

Aim to maintain minimum lab-based resuscitation targets:

Aim to maintain minimum lab-based resuscitation targets:

|

Targets |

Hemoglobin >80 g/L |

INR <1.8 |

Fibrinogen >1.5 g/L |

Platelets >50 x109/L |

Calcium >1.15 mM |

|

Treatment |

RBCs |

Frozen Plasma (FP) or Prothrombin Complex Concentrates (PCCs) |

Fibrinogen Concentrate (FC) |

Platelets |

Calcium |

- Recommended lab-based resuscitation targets:

|

Recommended Resuscitation Targets |

Ontario Regional 2019 MHP |

European 2019 Guideline |

World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA) 2012 Guideline |

|

Hemoglobin |

>80 g/L |

70-90 g/L |

>80 g/L |

|

INR |

<1.8 |

<1.5 |

<1.5 |

|

Fibrinogen |

>1.5 g/L |

>1.5-2 g/L |

>1.0 g/L |

|

Platelets |

>50 x109/L |

>50 x109/L; >100 x109/L if ongoing bleeding and/or TBI |

>75 x109/L; >100 x109/L if multiple high-energy trauma, CNS injury, and/or platelet function abnormality |

|

Calcium |

>1.15 mmol/L |

>1.1 mmol/L |

>1.13 mmol/L |

Standard approach to blood component delivery is applicable to most large adult hospitals:

|

Blood Pack |

Standard Approach |

Modifications for Smaller Centres |

|

Box 1 |

4 RBCs |

4 RBCs |

|

Box 2 |

4 RBCs, 4 FP |

4 RBCs, 2000 IU PCCs, 4 g FC |

|

Box 3 |

4 RBCs, 2 FP, 4 g FC |

4 RBCs, 2000 IU PCCs, 4 g FC |

|

|

PLTs should be transfused based on count (recent guidelines suggest this is preferable to empiric transfusion) |

If no PLTs, order from Canadian Blood Services (CBS) |

- For smaller hospitals with limited blood inventory, consider

- PCCs 2000 IU can be substituted for coagulation factor replacement (e.g., when no thawing device or no plasma stocked in inventory)

- Fibrinogen replacement should be given concurrently with PCCs unless the fibrinogen level is known to be ≥1.5 g/L

- Transfer patient promptly to a centre capable of definitive hemorrhage control

- Pediatric institutions will require age- and weight-based MHP

Other transfusion considerations:

- When patient’s blood group is unknown, transfuse group O Rh negative RBC to females under the age of 45 years and O Rh positive RBC to all other patients

- When patient’s blood group is unknown, transfuse group AB plasma

- Switch to patient’s group-specific RBC and plasma as soon as blood group is available

- To avoid hypothermia, transfuse RBC and plasma through a blood warmer

- To avoid inadvertent component wastage, blood components should be transported and stored in appropriate temperature-controlled, validated containers until ready to transfuse

- Take care to perform required pre-transfusion check to avoid mistransfusion

- This means that patients must have an identification bracelet with unique identifiers

- This also means that patient’s unique identifiers should not be changed until after MHP has been completed

- If available, use positive patient identification technology to perform pre-transfusion check

- Return blood components to transfusion medicine lab if no longer necessary

Potential risks of transfusion should be discussed

- Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO)

- Hyperkalemia

- RBC alloimmunization in women of child-bearing potential, which may result in hemolytic disease of the fetus/newborn; counsel to undergo RBC antibody screening 6 weeks and/or 6 months after transfusion

References:

- Bouzat P, Ageron FX, Charbit J, et al. Modelling the Association Between Fibrinogen Concentration on Admission and Mortality in Patients With Massive Transfusion After Severe Trauma: An Analysis of a Large Regional Database. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):55.

- Callum JL, Yeh CH, Petrosoniak A, et al. A Regional Massive Hemorrhage Protocol Developed Through a Modified Delphi Technique. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(3):e546-561.

- Dzik WH, Blajchman MA, Fergusson D, et al. Clinical Review: Canadian National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products--Massive Transfusion Consensus Conference 2011: Report of the Panel. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):242.

- Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of Plasma, Platelets, and Red Blood Cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 Ratio and Mortality in Patients With Severe Trauma: The PROPPR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471-482.

- Mesar T, Larentzakis A, Dzik W, et al. Association Between Ratio of Fresh Frozen Plasma to Red Blood Cells During Massive Transfusion and Survival Among Patients Without Traumatic Injury. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):574-580.

- Nascimento B, Callum J, Tien H, et al. Effect of a Fixed-Ratio (1:1:1) Transfusion Protocol Versus Laboratory-Results-Guided Transfusion in Patients With Severe Trauma: A Randomized Feasibility Trial. CMAJ. 2013;185(12):E583-589.

- Rao S, Martin F. Guideline for Management of Massive Blood Loss in Trauma. Update in Anaesthesia. 2012;28(1):125-129.

- Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, et al. The European Guideline on Management of Major Bleeding and Coagulopathy Following Trauma: Fifth Edition. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):98.